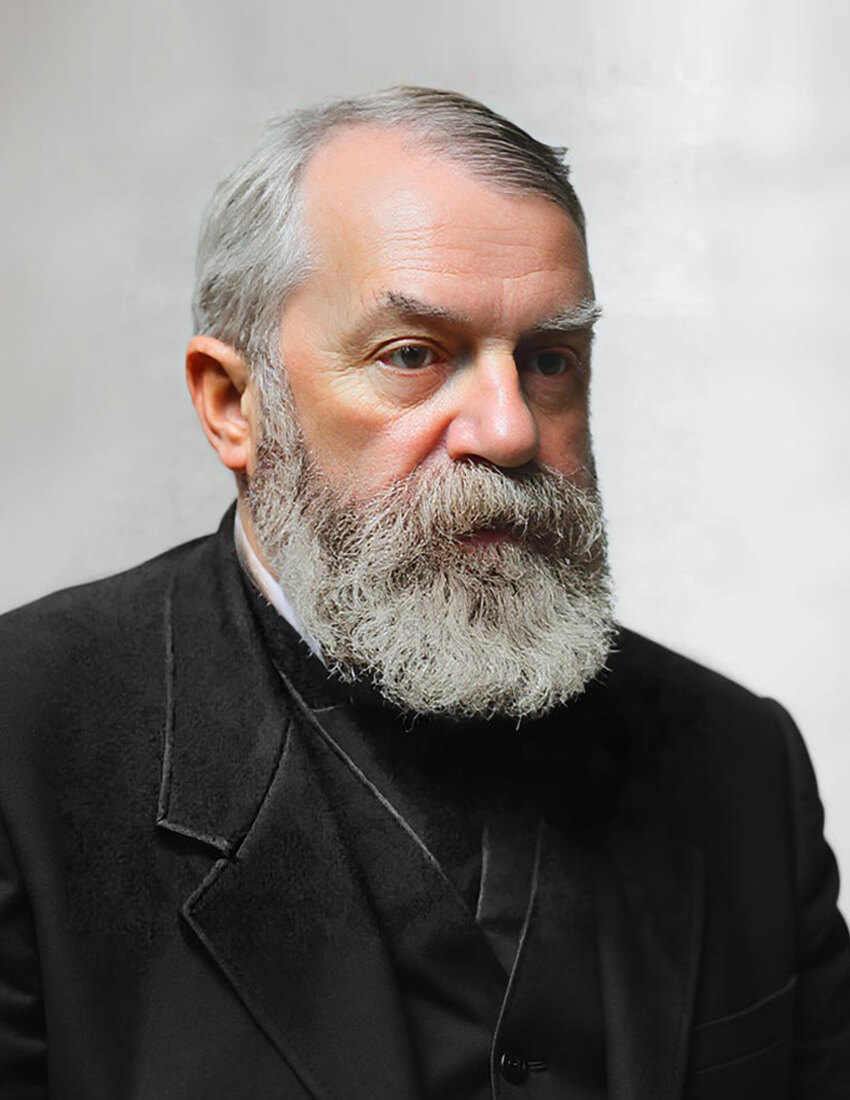

Born: August 28, 1840, Edinburg, PA.

Died: August 13, 1908, Brooklyn, NY.

Ira D. Sankey

Hymns by Ira D. Sankey

Faith Is the VictoryHiding in Thee

A Shelter in the Time of Storm

The Ninety and Nine

Under His Wings

Sankey himself sings his song The Ninety and Nine in this 1898 historic recording. Listen to Homer Rodeheaver’s version years later.

Gypsy Smith

A Romani (also called Roma) refers to a member of an ethnic group that originated in northern India and migrated to Europe centuries ago. They are traditionally nomadic people who have faced significant persecution throughout history.

In the 1800s context of the Sankey story, they were often called “Gypsies” – though this term is now considered outdated and sometimes offensive. That’s why the evangelist Rodney Smith was known as “Gypsy Smith” – he was of Romani heritage.

The Romani people have their own distinct culture, languages, and traditions. In Sankey’s time, many lived in traveling communities or camps, which is why the story mentions him visiting a “Romani camp” in Epping Forest near London.

The Great Connector

A musing on Sankey’s unique position in Christian hymnody

There are moments in history when God places certain individuals at the center of His work, not as the primary actors, but as the vital connectors who weave separate threads into a magnificent tapestry. Ira Sankey was precisely such a man—a humble singer who became the unlikely hub around which the golden age of American gospel hymnody revolved.

Consider the remarkable web of relationships that surrounded this Pennsylvania coal country boy. He worked directly with Philip P. Bliss on “Gospel Hymns and Sacred Songs” in 1876, then continued the series with James McGranahan and George C. Stebbins through five more volumes until 1894. When the tragic Ashtabula train disaster claimed Bliss’s life in 1876, Sankey was there to ensure that Bliss’s final hymn “My Redeemer” found its way to publication through McGranahan’s musical setting.

His “Sacred Songs and Solos” became the repository for nearly every significant hymn writer of his era. The final 1200-song edition included settings for Horatius Bonar, Fanny Crosby, Elizabeth C. Clephane, Robert Lowry, John Greenleaf Whittier, Frances Ridley Havergal and many others. He didn’t just sing their words—he gave them wings through melodies that ordinary people could learn and love.

Even “It Is Well With My Soul,” though written by Horatio Spafford, found its voice through Sankey’s circle. He witnessed its creation, carried it to Bliss for musical setting, and through his publications and ministry, launched it into immortality. George Stebbins later recalled being “the last surviving member of the original group of men Moody had associated with him in his evangelistic work including Sankey, Whittle, Bliss, and James McGranahan”—clear evidence of how closely knit this musical brotherhood truly was.

Perhaps most remarkably, Sankey served as president of Biglow & Main from 1895 to 1908, America’s leading publisher of Sunday school music, giving him unprecedented influence over what hymns reached American churches. Through his hands passed the songs that would shape Protestant worship for generations.

Was this mere coincidence? Or did the same God who orchestrated the writing of “The Ninety and Nine” on a Scottish train also position Sankey as the great connector of His musical servants? In an age when revival fire swept across two continents, when the Gospel hymn was being born and refined, God needed someone who could recognize good music, nurture talented writers, and guarantee that the songs born in prayer would find their way to every church and every heart.

Ira Sankey was that someone—not just a singer, but a shepherd of songs, gathering the scattered melodies of his generation and weaving them into the soundtrack of the Christian faith. Through his friendships, his publications, and his ministry, the separate streams of 19th-century hymnody flowed together into one mighty river that continues to nourish souls today.

The train wheels clicked rhythmically along the Scottish rails as Ira Sankey settled into his seat for the journey between Glasgow and Edinburgh. It was 1874, and the American gospel singer was in the midst of what would become one of history’s most significant religious revivals. As he opened his newspaper, a poem tucked away in the corner caught his eye. The words spoke of a shepherd searching for one lost sheep among ninety-nine safe ones. Something stirred in Sankey’s heart as he read Elizabeth C. Clephane’s verses, and he carefully cut out the poem, placing it in his musical scrapbook. Neither he nor anyone else on that train could have imagined that within twenty-four hours, those printed words would be transformed into a beloved hymn of Christian history.

From Pennsylvania Coal Country to God’s Service

Ira David Sankey was born on August 28, 1840, in Edinburg, Lawrence County, Pennsylvania, along the banks of the Mahoning River in the heart of western Pennsylvania’s coal country. His father, David Sankey, was a man of many talents and deep faith—serving variously as a banker, editor, revenue collector, and even a member of the state Senate. Of English descent, David had also answered the call to be a Methodist lay preacher. Ira’s mother, Mary Leeper Sankey, brought Scotch-Irish heritage to the family and possessed the gift that would shape her son’s destiny: she taught young Ira his first hymn.

The Sankey household buzzed with the sounds of nine children, but it was the evening gatherings around the fireplace that left the deepest impression on young Ira. There, surrounded by his four brothers and four sisters, the family would lift their voices in song, creating a harmony that reflected the Methodist tradition of heartfelt worship. These moments of family singing became Ira’s first conservatory, though he would never receive formal voice training beyond a brief twelve-week session later in life with the renowned American music educators George Frederick Root, Lowell Mason, and William Bradbury.

Ira’s spiritual awakening began early, influenced by a man named Mr. Fraser who faithfully took him and Fraser’s own sons to Sunday school. But it was during revival meetings at King’s Chapel, about three miles from the Sankey home, that sixteen-year-old Ira experienced true conversion. The flame of faith ignited that day would burn brightly for the rest of his life.

In 1857, the family relocated to New Castle, Pennsylvania, where David Sankey assumed the presidency of the local bank. This move proved pivotal for young Ira, who quickly became a cornerstone of the Jefferson Street Methodist Episcopal Church. His natural leadership abilities and developing musical talents were immediately recognized, leading to his election as Superintendent of the Sunday School, director of the Choir, and eventually a class leader. It was Ira who championed the installation of the first organ in his church, demonstrating an early understanding of music’s power to enhance worship.

During these formative years, Ira’s voice developed what would later be described as an “exceptionally strong baritone” with a “full, rich, and resonant quality.” Encouragement came from established musicians of the day, particularly songwriter Philip Philips and the influential William Bradbury, who recognized the young man’s potential for ministry through song.

War, Work, and the Call to Serve

When President Lincoln issued his call for volunteers in the spring of 1861, twenty-year-old Ira Sankey answered without hesitation, enlisting in the 22nd Pennsylvania Regiment. His military service took him to Maryland, where the horrors of war could not diminish his commitment to faith. Even in the camps, Sankey organized religious meetings and led soldiers in singing hymns that brought comfort amidst the chaos of conflict. This experience of using music to minister to hearts in desperate circumstances would prove invaluable training for his future calling.

After completing his military service, Sankey returned to New Castle and took up work as a collector for his father’s business. Yet his heart remained drawn to spiritual matters, and he found himself frequently attending conventions and rallies throughout Pennsylvania and eastern Ohio. His cultivated voice made him increasingly sought after as a gospel singer in these gatherings.

On September 9, 1863, Ira married Frances V. Edwards (known as “Fanny”), a member of his choir and the daughter of the Honorable John Edwards, a State Senator. Their union would be blessed with three sons: Henry, Edward, and Ira Allan Sankey (often referred to as Allen or I. Allen Sankey). Of these sons, Allen followed in his father’s footsteps as a composer and editor of gospel music, carrying forward the family’s musical legacy.

The Meeting That Changed Everything

The course of Ira Sankey’s life changed forever in June 1870, at an international YMCA convention in Indianapolis where he served as a delegate. When the congregational singing began to drag and lose its spirit, Reverend Robert McMillen approached Sankey and asked him to take charge of the music. What happened next would echo through eternity.

As Sankey’s powerful baritone voice lifted in song, it stirred and enlivened the entire audience. Among those listening was a stocky, bearded evangelist named Dwight L. Moody, who was so moved by what he heard that he impulsively approached Sankey after the service. Without preamble, Moody asked the young singer to join him in Chicago for Christian work. Such a life-changing proposition required considerable thought, and Sankey was not prepared to make such a momentous decision on the spot.

Six months of prayer and contemplation passed before Sankey agreed to spend one week with Moody in Chicago. That trial week involved visiting the sick, holding noonday prayer meetings, and conducting services throughout the bustling city. It quickly became apparent to many that Sankey’s work was divinely appointed to complement Moody’s preaching ministry. In early 1871, Sankey made the commitment to partner with Moody full-time.

Their early collaboration was tested by fire—literally. On October 8, 1871, the Great Chicago Fire swept through the city, destroying Moody’s church and scattering their newly formed ministry. Sankey returned to Pennsylvania, but two months later, Moody urged him to return to Chicago. After much prayer, Sankey accepted, moving his family to Chicago in October 1872. This decision marked the beginning of a partnership that would transform evangelism on both sides of the Atlantic.

The collaboration between Moody and Sankey was beautifully complementary. Where Moody possessed the gift of plain-spoken preaching that cut straight to the heart, Sankey brought a pleasing appearance and expressive countenance that radiated inner light. So complete was Moody’s trust in his musical partner that he put Sankey in charge of the ministry at the Tabernacle during his second tour of England.

Across the Atlantic – Revival Fire Spreads

In June 1873, Moody and Sankey embarked on their first joint visit to England, beginning with small gatherings in York. What started modestly soon grew beyond anyone’s expectations. Word of the American evangelists spread like wildfire, and within months they were preaching and singing before crowds of 20,000 in London. Their British campaign lasted from 1873 to 1875, taking them to major cities across England, Scotland, and Ireland.

The success of their first British tour led to subsequent campaigns, including a major effort from 1881 to 1884 that saw them holding meetings in hundreds of locations, with ninety-nine meetings in Scotland alone. Such was their popularity that for the 1881 tour, they employed an innovation in mass-meeting logistics: a portable 5,000-seat tabernacle that traveled from city to city, bringing the revival directly to the people.

Their ministry extended globally, including a significant campaign at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, where they brought the Gospel message to visitors from around the world. Through it all, Sankey’s role remained constant: to prepare hearts through song for the Word that Moody would proclaim.

A Prophetic Word to a Romani Boy

During a meeting in 1874 on Burdette Road in London, Sankey and Moody decided to visit a Romani camp in Epping Forest. Among the weathered faces and modest dwellings, Sankey’s attention was drawn to a young Romani boy. Moved by the Spirit, Sankey placed his hand on the child’s shoulder and spoke words that seemed to echo with prophetic power: “May the Lord make a preacher of you, my boy.”

Fifteen years passed before the full significance of that moment was revealed. In Brooklyn, Sankey encountered an English evangelist named Rodney “Gypsy” Smith, whose powerful preaching was winning souls across America and Britain. As the two men spoke, Smith made a startling revelation: he was that very Romani boy from the Epping Forest camp, and Sankey’s prophetic words had profoundly shaped his calling to ministry. What seemed like a simple blessing spoken to a child had actually been God’s way of launching another powerful voice for the gospel.

“The Ninety and Nine” – A Song Born of Providence

Sankey maintained what he called a musical “scrapbook,” carefully collecting poems and musical ideas that might someday be useful in ministry. It was this habit that led to one of the most remarkable moments in hymn history. As his train traveled between Glasgow and Edinburgh during the 1873-1875 Scottish tour, Sankey discovered Elizabeth C. Clephane’s poem about the lost sheep in his newspaper. The words, based on Jesus’ parable from Luke chapter fifteen, immediately captured his imagination.

Excited by his discovery, Sankey attempted to share the poem with Moody, but found his ministry partner completely engrossed in reading a letter. Undeterred, Sankey carefully cut out the poem and placed it in his scrapbook, not knowing that divine providence was already orchestrating its destiny.

The next day brought a noon meeting at the Free Assembly Hall in Edinburgh. Moody had just finished delivering a powerful message on “The Good Shepherd” when he turned to Sankey and requested a solo that would complement the sermon’s theme. Sankey felt a sinking sensation—he had nothing prepared that seemed appropriate for such a moment.

Then, as he later described it, he felt a voice telling him to “Sing the hymn you found on the train.” What happened next became the stuff of legend. Sankey lifted his heart in prayer, “asking God to help me so to sing so that the people might hear and understand.” Placing his hands on the organ, he struck the chord of A flat and began to sing words he had never before sung to a melody that was being born in that very moment.

“Note by note the tune was given,” Sankey later recalled, “which has not changed from that day to this.” As the final notes faded away, “a great sigh seemed to go up from the meeting,” and Sankey knew that his song had reached the hearts of his Scottish audience. Moody, visibly moved, remarked that he had never heard anything like it. When Sankey explained that he had tried to read those very words to him just the day before, both men recognized the hand of God in the timing of it all.

The hymn’s impact was immediate and lasting. “The Ninety and Nine” became one of the signature songs of the Moody-Sankey campaigns and would eventually find its way into hymnals around the world, carrying its message of God’s relentless love for the lost to countless generations.

The Art and Heart of Sacred Song

Sankey’s approach to ministry through music was grounded in deep conviction about the spiritual power of song. His philosophy was beautifully expressed in his own words: “Before I sing, I must feel, and the hymn must be of such kind as I know I can send home what I feel into the hearts of those who listen.” This wasn’t merely performance; it was spiritual warfare waged through melody and verse.

His technique was equally thoughtful. “You’ve got to make them hear every word and see every picture,” he explained. “Then you’ll get that silence of death, that quiet before God.” Sankey achieved this through crystal-clear diction, careful pacing, and his habit of accompanying himself on a small portable reed organ. He insisted on soft accompanying music that would support rather than overwhelm the words, understanding that the message must always take precedence over the melody.

Despite lacking formal conservatory training, having received only that brief twelve-week session with Root, Mason, and Bradbury, Sankey possessed what was described as an “exceptionally strong baritone” with sound vocal technique. Yet contemporary observers recognized that his true power lay deeper than mere vocal ability. As one newspaper review noted, “he expresses the gospel message with exquisite skill and pathos… but the secret of Mr. Sankey’s power lies not in his gift of the song but in the spirit of which the song is only the expression.”

Sankey himself understood his role perfectly, explaining the partnership this way: “Moody reaches men’s hearts with words that are spoken, while I reach them with words that are sung.” This wasn’t competition but collaboration, two instruments in God’s orchestra playing in perfect harmony to accomplish His purposes.

Sacred Songs That Shaped a Generation

While Sankey occasionally penned his own lyrics, his true genius lay in setting the poetry of others to simple, memorable melodies that ordinary people could easily learn and sing. His compositional method relied heavily on what he called “inspiration”—he would jot down melodies in his notebook as they came to him, then develop them later when the right words demanded musical expression.

Sankey collaborated with the finest hymn writers of his era, creating musical settings for verses by Horatius Bonar, Fanny Crosby, Elizabeth C. Clephane, Robert Lowry, John Greenleaf Whittier, and Frances Ridley Havergal. His settings became recognizable for their simple melodies and strong, vigorous rhythms that reflected the popular music of the time while maintaining the dignity appropriate for worship.

The publishing history of Sankey’s work tells the story of unprecedented success. “Sacred Songs and Solos,” first published in 1873, eventually expanded to include 1,200 items and sold over 50 million copies worldwide. His collaboration with P. P. Bliss on “Gospel Hymns and Sacred Songs” began in 1875 and grew to include five supplements, culminating in a complete six-part edition published in 1894.

Among Sankey’s most enduring compositions were “Hiding in Thee,” set to words by W. O. Cushing in 1876; “A Shelter in the Time of Storm,” based on a poem by V. J. Charlesworth; and “Faith Is the Victory,” written to lyrics by J. H. Yates in 1891. Each of these hymns demonstrated Sankey’s gift for creating melodies that seemed inevitable—so perfectly matched to their words that it became impossible to imagine the text set to any other tune.

Remarkably, Sankey chose to use the proceeds from these publications for charitable purposes rather than personal enrichment. This decision reflected his understanding that his gift was held in stewardship for God’s kingdom, not for his own financial gain.

British poet John Betjeman later observed that Sankey had mastered “that well-known principle of denying the devil all the best tunes,” referring to his use of popular, accessible melodies that could compete with secular music for a place in people’s hearts and minds.

When Darkness Fell

The partnership that had blessed millions came to an end on December 22, 1899, when Dwight L. Moody passed away. Sankey’s grief was profound, but he channeled it into one final tribute to his beloved friend and partner. At Moody’s funeral, Sankey composed and performed “Out of the Shadowlands,” a fitting farewell to the man who had called him from obscurity to international ministry.

After Moody’s death, Sankey attempted to continue the work alone, but mounting health problems made such efforts increasingly difficult. Beginning in 1903, severe glaucoma began stealing his sight, and by his final years he was nearly completely blind. Yet even in this trial, Sankey demonstrated the same faith that had sustained him throughout his ministry. He completed his autobiography, “My Life and Sacred Songs,” in 1906, dictating the final chapters as his vision failed.

The man who had spent decades helping others see spiritual truth through song now walked in physical darkness, yet his spirit remained undiminished. He continued limited ministry and editorial work as his health allowed, always ready to share the hope that had never failed him.

A Moment in Jerusalem

In 1898, Sankey made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land that produced one of the most touching images of his later ministry. Standing atop the Tower of David in Jerusalem, this American gospel singer lifted his voice to sing Psalm 121 to a puzzled Ottoman guard who could not understand the words but could not help being moved by the spirit behind them. It was a perfect picture of how Sankey’s songs transcended all boundaries of language, culture, and nationality to touch the universal human heart.

“It Is Well With My Soul” – Born from Deepest Sorrow

Among the many souls touched by Sankey’s ministry was Horatio Gates Spafford, a successful Chicago lawyer and Presbyterian elder who moved in the same evangelical circles as Moody and Sankey. The Spaffords were faithful supporters of the revival work, but their faith would soon face a test that few could imagine surviving.

The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 had already dealt the Spafford family a severe financial blow, wiping out much of Horatio’s real estate holdings. Two years later, in 1873, Spafford arranged for his wife Anna and their four precious daughters to travel to Europe, where they would assist with Moody and Sankey’s evangelistic campaigns. Business matters required Horatio to remain behind, planning to join his family later.

On November 22, 1873, the unthinkable happened. The SS Ville du Havre, carrying Anna and the four Spafford daughters, collided with another vessel in the Atlantic and sank beneath the cold waters. All four children perished in the tragedy. Anna survived, and her telegram to her husband became one of the most heartbreaking messages ever sent: “Saved alone. What shall I do?”

Horatio immediately sailed to join his grieving wife, his ship passing over the very waters where his daughters had died. Popular legend tells us that he wrote “It Is Well With My Soul” at that spot on the ocean, but Sankey’s own memoirs reveal a different, more remarkable truth.

The hymn was actually born three years later, in 1876, in the Spafford home in Chicago where Sankey was staying. As an eyewitness to the hymn’s creation, Sankey watched Horatio work thoughtfully through the verses, carefully revising and refining the words that would become his testimony of faith through unbearable grief. The hymn wasn’t written in a moment of sudden inspiration on the Atlantic, but rather grew from three years of wrestling with sorrow and finding God’s peace in the midst of it.

Sankey recognized the profound power of Spafford’s words and took the completed poem to Philip P. Bliss, his gifted collaborator and fellow hymnwriter. Bliss composed a melody that perfectly captured the hymn’s spirit of peaceful surrender, naming the tune “Ville du Havre” in memory of the ship that had carried the Spafford children to their eternal home. When Bliss first sang the complete hymn at a meeting in Farwell Hall in 1876, the audience was deeply moved by its message of trust in God’s providence through life’s darkest valleys.

That same year, Sankey and Bliss published “It Is Well With My Soul” in their influential collection “Gospel Hymns No. 2,” ensuring that Spafford’s testimony would reach far beyond Chicago’s evangelical circles. Through the vast ministries of Moody and Sankey, which spanned both America and Britain, the hymn quickly spread throughout the Protestant world.

The song’s enduring power lies not in when or where it was written, but in the profound truth it proclaims: that even when earthly circumstances bring unimaginable loss, the soul can find perfect peace in God’s unchanging love. For nearly 150 years, those words have comforted the grieving and strengthened the faith of countless believers. The hymn has appeared in over 500 hymnals and been translated into dozens of languages, its message transcending every barrier of culture and denomination.

Sankey and Moody had been instruments of comfort to the Spaffords in their darkest hour, and through their ministry, Horatio’s hard-won testimony became a gift to the world. Once again, God had used ordinary friendship and faithful service to birth something extraordinary—a hymn that continues to whisper peace to troubled hearts everywhere.

The Song Continues

On August 13, 1908, at the age of 67, Ira David Sankey’s voice was finally stilled. He died in Brooklyn, New York, survived by his widow Frances and two of his sons. His funeral was held at LaFayette Avenue Presbyterian Church before his burial at Green-Wood Cemetery. Newspapers across America and Britain carried word of his passing, marking the end of an era in evangelical music.

Yet in another sense, Sankey’s song continues to this day. His roughly 200 tunes and arrangements included in the final edition of “Sacred Songs and Solos” established the template for evangelistic songbooks that would be copied for generations. He standardized the songleader-plus-reed-organ model that became the norm for revival meetings well into the twentieth century.

More importantly, hymns like “The Ninety and Nine,” “Hiding in Thee,” “A Shelter in the Time of Storm,” and “Faith Is the Victory” continue to appear in modern hymnals, their simple melodies still carrying eternal truths to new generations of believers. His 1980 induction into the Gospel Music Hall of Fame officially recognized what millions of Christians had long known: Ira Sankey’s voice had carried revival to the world.

Perhaps the most beautiful aspect of Sankey’s legacy is how perfectly it reflects God’s economy of grace. He was not a formally trained musician, not a seminary graduate, not a man of great theological learning. He was simply someone who believed that “before I sing, I must feel,” and who was willing to let God use that sincere heart to bless the world.

From that moment on a Scottish train when he carefully cut out a newspaper poem, to the countless revival meetings where his baritone voice prepared hearts for the gospel, to the millions of hymnals that carried his melodies into churches around the globe, Ira Sankey’s life reminds us that God delights in using ordinary faithfulness for extraordinary purposes. His songs continue to echo the truth he lived: that no matter how far we may wander, there is a Shepherd who will never stop searching until He brings us safely home.